The Future of Growth

Apr 2nd, 2019 | By admin | Category: Economics and GDPBy Dr. Milton Saier and Art Elphick, guest writers.

Recent articles call for higher birthrates to spur economic growth. But upon observing the human impact on our resources and environment, many scientists consider even current economic and population growth rates unsustainable.

Our world has just experienced prenominal growth. Since 1900, the population has grown by a factor of 4.75 and GWP (Gross World Product) has grown by a factor of 108.8.* What’s more, while the GWP keeps doubling every twenty years, we keep looking for ways to speed up the pace.

Many seem to think that world population and economic growth can keep expanding indefinitely. Would that be possible? How much longer can this growth go on?

Some economists and scientists now warn of serious consequences. On top of rapid resource depletion, we have species extinctions, problems with greenhouse gases and toxic pollution, deforestation, soil destruction, desertification, dying reefs, over-fishing, delta dead zones, over- taxed water supplies, and more. All of these problems are fueled by human activities. As we search for ways to reverse them, they only grow worse. Perhaps we now must reign in some of that expanding human activity. And yes, that does mean reducing some types of growth.

Recent articles call for higher birthrates. What’s more, they seem to be winning the day. As the world population continues to grow, 56 low-birthrate nations now offer incentives to have more babies – very sizable incentives in several cases. Some articles note a measure called the dependency ratio which tracks the percentage of two groups who mostly rely on working-age people for support: children under age 14 and adults over age 65. They claim that a “birth dearth”will result in too few working-age people to support a growing percentage of elderly people, and they warn that declining birthrates will drag down the economy.

Nations might address such concerns by importing and training, if need be, workers from places where people don’t earn enough to meet their basic needs. That they instead want more babies probably reflects a fear that accepting outsiders would upset their traditional ways of life.

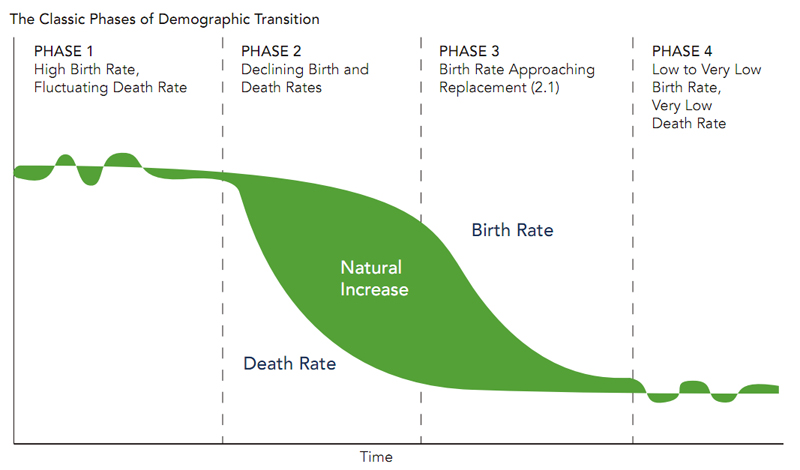

But is it really true that low birthrates create an economic burden? In 2009 a study by Steven Sinding of Guttmacher Institute confirmed the findings of a multi-year series of studies by Princeton’s Ansley Coale and Harvard’s David Bloom. These studies looked at nations around the world that graduated from developing status to developed status – including China and all of the “Asian Tigers.” They all experienced rapid per-capita GDP gains only after achieving low birthrates.

A 2012 factsheet called Attaining the Demographic Dividend explains that having fewer dependent children allows families to spend a smaller portion of their incomes on the basic essentials required for day-to-day survival, leaving them with more to spend on things that raise their standard of living. They have more to spend on their homes, more to spend on each child, and more to invest. Their investments allow businesses to modernize for greater productivity and expand with more specialized jobs that pay better wages. Governments can then tax those gains to improve schools, roads and other services – all of which also contribute to economic growth.

None the less, articles published in the New York Times and other places have claimed that economic growth requires population growth – that we must endlessly expand our population to keep the economy humming. If that were true, China could not have averaged a compounded annual growth rate of 10.3 percent during the thirty-two-year period (1982-2014) that it limited urban families to just one child. In the U.S, our record growth rates in the 1960s occurred when our dependency ratio was also at a high.

However, we often do find that economic growth triggers population growth. People seeking jobs move to places that offer good jobs. The growing populations in such places create a demand for more housing, infrastructure, and services, all of which further grow the area’s economy.

But not all of that growth improves the well-being of the region or its citizens. Much of it involves just catching up with the needs of growing populations for homes, schools, roads, etc. Until the supply of those things catches up with the growing demand, the cost of living rises.

Places with static or falling populations, such as Japan and Italy, usually have less need for more housing, infrastructure, and public services. Even where such places generate less income per capita, people can spend more of that income on improving their homes, communities, and quality of life – including elder care and health care. If our dependency concern is for people on fixed incomes, elderly people often find the low-growth areas most affordable, and the low-growth areas benefit from what they spend there.

Of course, a region must generate enough income to allow its population to stay. Every region must import appliances, building equipment, medical supplies, etc. from other places. To pay for such things, that region must either offer goods to sell to outsiders, or it must find people who bring in money from outside the area.

Many economists and scientists now question whether endless growth in production, construction, transport, and travel is desirable or even possible.

To monitor economic activity, economists track the outputs of each business sector. Gross World Product (GWP) and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) measure the yearly dollar value of all economic activity. Both measures lump all types of economic activity into a single dollar value. But they do not consider such values as the quality, social benefit, sustainability or equitable distribution of what is produced. Many economic activities damage our environment and squander our reserves of non-renewable resources. Neither GWP nor GDP take these factors into account.

People have some basic needs for transportation, homes, appliances, utilities, food, travel and services. But making these things consumes non-renewable resources, and often produces pollution and CO2. Consuming any non-renewable resource reduces our reserves by an equal amount, and the pollution we generate drives down the livability and aesthetic quality of our environment.

Economist Simon Kuznets proposed replacing GWP with an index of sustainable economic welfare called the Genuine Progress Indicator. While other economists have yet to embrace the GPI or refer to it often, Kuznets made an important point. We need an indicator with GDP status to focus public awareness on meeting sustainable quality-of-life objectives. A good indicator would not just assess the cost and quantity of things we produce; it would also assess the benefits of what we produce in meeting the present and future needs of our people and our society.

Kuznets is not the only one trying to steer the mainstream toward a more sustainable economy. An Internet search will list books, articles and organizations that share his goals.

The limits-of-growth concept may seem to imply that we have had enough growth, and now we must downsize. But, rather than slow progress, we need to redefine it.

Progress is not just producing more material goods through increased mechanization. It also comes when we replace old technology with new and more sustainable technology. For example, when we invest in mass transit, fuel-stingy cars, ecologically advanced fish hatcheries and farms, regionally sourced products, and clean energy technologies, we reduce the need for products and shipping that consumes our scarce resources and/or pollutes our environment.

Many purchases (and jobs) consume few non-renewable resources and produce no hazardous byproducts. For example, services such as teaching and counseling, daycare, eldercare, health and mental health care, environmental cleanup and restoration, and recycling and refurbishing – all offer sustainable consumer benefits and work opportunities.

But we need some changes in our buying habits. To make our economy more sustainable, we need fewer avoidable trips in gas-run cars, planes, and yachts; fewer disposable products made from non-renewable ores or oils; less consumption of open-ocean fish to prevent the depletion of the low breeding stocks; and fewer transport-intensive imports – especially bulk goods available from local sources at reasonable prices. We must also end the construction of sprawl homes that require long commutes and take land from our remaining natural habitats. Wasting less on these things allows us to invest more in new products and jobs designed to reduce resource depletion and pollution.

The World Trade Organization claims that the richest twenty percent consume about eighty-six percent of the world’s resources. If the very rich squandered less on personal jets, personal yachts, and multiple spacious homes, the poor could enjoy quality of life improvements without a net growth of our sustainability problems.

We also must do all we can to help reduce birthrates in developing nations so that they can enjoy the well documented dividends that result from smaller families. And wherever birthrates fall, we should consider that a necessary step toward achieving economic sustainability.

*Calculated from data in the CIA World Factbook

About the authors:

Dr. Milton Saier is a Professor of Molecular Biology in the Division of Biological Sciences at UC San Diego.

Art Elphick is a retired technical writer and college instructor who gives quarterly sustainability seminars at UC San Diego

![[Photo by Flickr user Images Money via Creative Commons license]](http://populationgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/money-300x200.jpg)