“Have Children for the Country” – Changing Misguided Assumptions on Declining Population Growth

Jan 8th, 2019 | By admin | Category: Economics and GDPBy Suzanne York.

It is commonly accepted by the ‘powers that be’ that continued population growth is a great thing and declining population growth is terrible. This assumption permeates the global economy mentality, where constant growth of people and markets is the mantra.

![View of Tokyo [Photo: Creative Commons license, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tokyo_from_the_top_of_the_SkyTree.JP]](http://populationgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Tokyo-300x180.jpg)

View of Tokyo

[Photo: Creative Commons license, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tokyo_from_the_top_of_the_SkyTree.JP]

Reversing Course

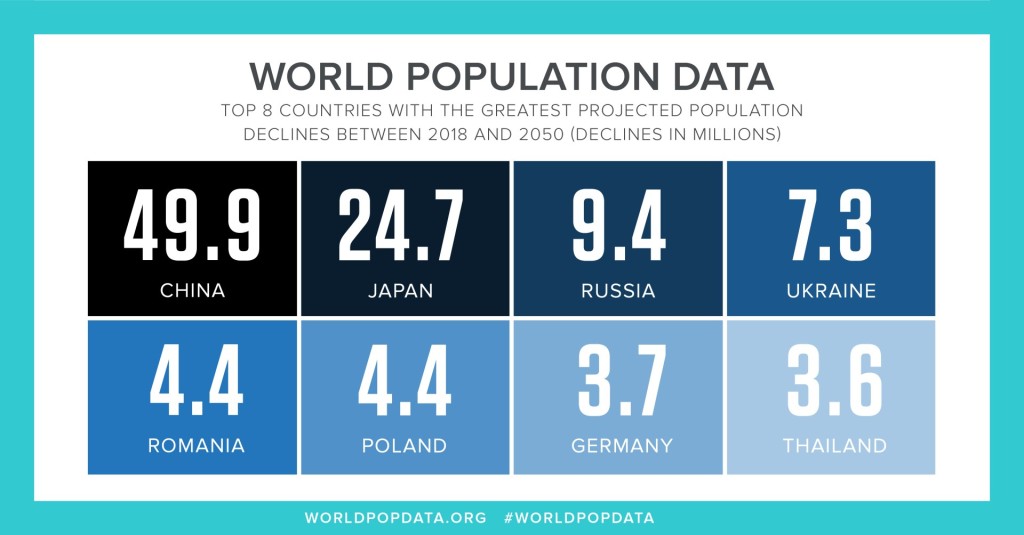

China, the focus of so much attention due to its former draconian one-child policy, is now in the news for declining population numbers. According to a Chinese research organization, if the nation’s fertility rates remain unchanged, the population could fall from nearly 1.4 billion today to 1.17 billion by 2065. This is striking terror in the world’s second-largest economy.

So much so that China is now calling on citizens to “have children for the country.”

A report published by the China Academy of Social Sciences found that “From a theoretical point of view, the long-term population decline, especially when it is accompanied by a continuously ageing population, is bound to cause very unfavourable social and economic consequences.”

Bloomberg Newscalled it “China’s Debate Over a Shrinking Birth Rate Highlights Growth Concerns.” Like many countries, such as Japan and Italy, China is now experiencing an aging population. In 2017, China’s State Council projected that about one-quarter of its population would be 60 or older by 2030, compared with 13 percent in 2010.

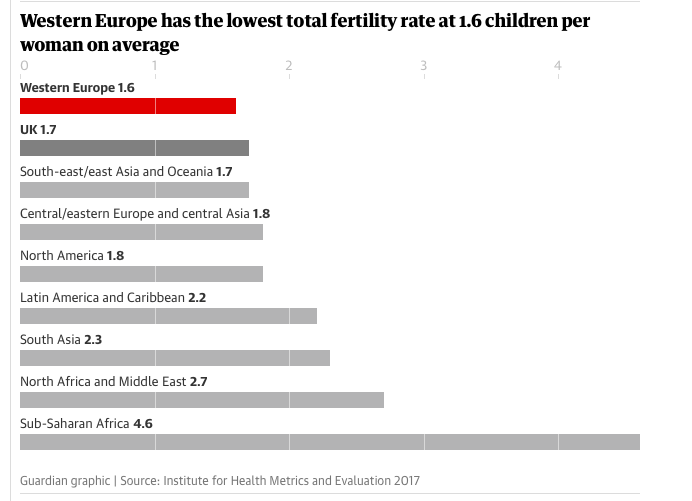

South Korea, too, is greatly concerned about aging population. It has one of the world’s lowest fertility rates, with a total fertility rate of 1.1(and could be as low as .96 (the World Health Organization defines total fertility rate, or TFR, as the total number of children born or likely to be born to a woman in her lifetime if she were subject to the prevailing rate of age-specific fertility in the population).

The government offers cash incentives for people to have kids. See Business Insider’s article, “South Korea’s fertility-rate crisis is so dire that the country is offering cash to entice rich people to have kids” to get an idea of the fears about low population growth. Reuters reported that in “just over a decade, South Korea has spent the equivalent of a small European economy trying to fix its demographic crisis, yet birthrates have dropped to the lowest in the world.”

The global total fertility rate stands at 2.4, which is considered just above “replacement” level.

It seems that even monetary incentives might not be able to tamp the desire for a smaller family. It could be that people in countries experiencing low population growth rates just want to have fewer kids, and most importantly, want to be able to support them with school, health care, nutrition, etc.

Unchartered Waters

This is new territory, and we don’t really know yet what it means, at least for the economy. But in general terms, low population growth normally translate into higher standards of living, less traffic, less competition for jobs and schools, and more open space and land for nature. And there are alternatives to unsustainable economic growth.

There was a fascinating interview recently in the UK Guardian, with Professor Sarah Harper of the University of Oxford, in which she argues that declining populations might be a good thing. Harper, who is an expert in demographic and population change, told the Guardianthat fears that a declining total fertility rate would see a country fall behind, especially economically, were groundless and are old ways of thinking.

“All the evidence is, that if families, households, societies, countries have to deal with large numbers of dependants, it takes away resources that could be put into driving society, the economy etc,” Harper said, adding that the “problem” of an ageing population also needed to be reconsidered, not least because technology to support dependants was advancing while people were staying in good health for longer. “It is much easier to enable older adults to stay upskilled and healthy and in the labour market than it is to say to women ‘oh you have got to have children’.”

Harper also warned – correctly – that the focus on boosting population growth was outdated and potentially bad for women.

Other researchers have found that smaller populations can lead to more sustainable societies. Last year, ecologists writing in the scientific journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution noted that “As the nations of the world grapple with the task of creating sustainable societies, ending and in some cases reversing population growth will be necessary to succeed. Yet stable or declining populations are typically reported in the media as a problem, or even a crisis, due to demographic ageing.”

The authors wrote that “The social, economic, and environmental benefits associated with stable or even declining populations, more than compensate for the economic costs of supporting an ageing population.” They found many benefits to an ageing society, including:

- Rising wages for workers and higher wealth per capita

- Less crowding and reduced stress in populated areas

- Greater protection of green spaces and improved quality of life

Perhaps most importantly, declining population growth is one key solution to addressing climate change, (especially if it resulted in less consumption).

The Year 2750 is a Long Way Off

The Business Insider article above mentioned a study commissioned by South Korea’s National Assembly that found that South Koreans could “face natural extinction” by 2750 if the country’s fertility rate were to remain at 1.19.

Given centuries of human exploitation of the planet, it’s hard to fathom what the world will be like in 2050, much less in 2750. But if people are choosing to have smaller families, are living healthy and longer lives, and could possibly exist in balance with Nature, wouldn’t that be something to celebrate and strive for in 2019?

Suzanne York is Director of Transition Earth.