The Economics of Nature: The Need for Transformative Change

Feb 11th, 2021 | By admin | Category: Economics and GDPBy Suzanne York.

It was a blip for most news outlets, but a recent report out of the UK – led by Cambridge economist Professor Sir Partha Dasgupta – underscores the global biodiversity crisis and humans relationship with Nature. The fact that it comes from an economic viewpoint has its pros and cons, but is still a must-read report that lives up to its call for transformative change.

The headline message from The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review is that “We are part of Nature, not separate from it.” Unsurprisingly from an economic standpoint, Nature is still seen as an asset, though a precious one, but nonetheless an asset.

The report lays out some stark facts to make the case that if humans don’t change our ways, we will suffer. For example, take these two statistics:

- Humans, together with the livestock we rear for food, constitute 96% of the mass of all mammals on the planet.

- Only 4% is everything else – from elephants to badgers, from moose to monkeys. And 70% of all birds alive at this moment are poultry – mostly chickens for us to eat.

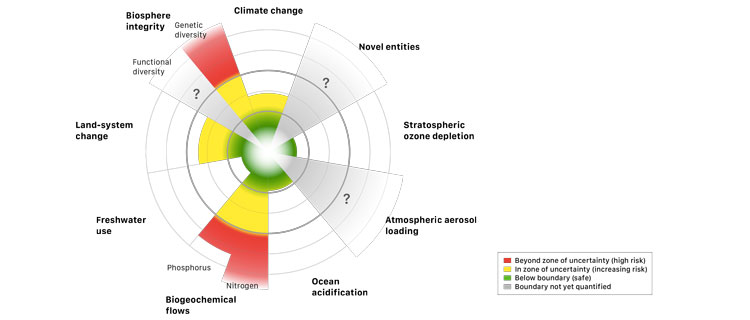

What does this mean for people? According to the report, “We are destroying biodiversity, the very characteristic that until recently enabled the natural world to flourish so abundantly. If we continue this damage, whole ecosystems will collapse. That is now a real risk.”

Why Care About Economics?

Our current global economic system is based on perpetual growth and exploitation of resources and cheap labor. It is how modern life is structured and for that reason we need to care about changing this system. The Dasgupta Review raises points not normally associated with the field of economics.

David Attenborough, who wrote the foreward to the review, states why it is critical for economists to address our biodiversity crisis:

Economics is a discipline that shapes decisions of the utmost consequence, and so matters to us all. The Dasgupta Review at last puts biodiversity at its core and provides the compass that we urgently need. In doing so, it shows us how, by bringing economics and ecology together, we can help save the natural world at what may be the last minute – and in doing so, save ourselves.

The Three Transitions

Briefly, amongst other things, the review lays out three necessary transitions to change course, and boldly calls for an effort similar to or greater than the Marshall Plan to protect biodiversity. That alone sets this review apart from many others.

Of the three transitions, the first one is the most important for people and Nature: ensuring that our demands on Nature do not exceed its supply, and that we increase Nature’s supply relative to its current level.

Land cleared for food production is a major driver of biodiversity loss. Addressing sustainable food production is clearly needed, so we stop exceeding Nature’s bounty. Decarbonizing energy systems is another transition that the world must undertake. People have taken Nature for granted for too long.

Fortunately, The Dasgupta Review is not shy to take on the issue of population growth, noting that as world population grows, meeting the need for sustainable food and energy systems will be more challenging. Heeding population growth projections is very important, calling it “a necessary exercise in the economics of biodiversity.”

The report’s authors clearly understand the need to include population growth but to promote women’s rights and family planning as a key solution to achieving a healthy population:

Growing human populations have significant implications for our demands on Nature, including for future patterns of global consumption. Fertility choices are influenced not only by individual preferences, there are also shaped by the choices of others. As well as improving women’s access to finance, information and education, support for community-based family planning programs can shift preferences and behavior, and accelerate the demographic transition. There has been significant underinvestment in such programs. Addressing that shortfall, even if the effects may not be apparent in the short-term, is essential. (emphasis added).

The other two recommended transitions are for changing measures of how we define economic success and transforming institutions and systems to enable change. Changing the entrenched GDP measurement would be a critical shift for the better, as it calculates both positives and negatives as growth. There are many existing proposals for new economic measurements to which we can turn and replace GDP.

As for institutions, upcoming conferences on climate change and the Convention on Biological Diversity offers opportunities to ‘set a new direction’ for Nature.

New Thinking

The Dasgupta Review is an in-depth look at how to change course within an economic framework. That may not be ideal for some (see section on payment of ecosystem services), but it is the system in which modern societies exist, and thus necessary to address how it alter the global economic system in a way that respects Nature. That said, it is still a product of that system and sees Nature as an asset, one albeit with “intrinsic worth.”

There’s no mention of what the world can learn from how indigenous people, many of who live within areas of immense biodiversity and sustainably manage natural resources. This review also does not consider more game-changing initiatives such as Nature Needs Half, or paradigm-shifting concepts like Rights of Nature. It’s probably a stretch for economists, but we are at a point where bold ideas should be implemented.

But for economists to write of transformative change that views Nature as more than just an economic good is encouraging, to say the least. In words attributed to Albert Einstein, “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” Global economics essentially encourages environmental devastation and doesn’t care about the opportunity cost of biodiversity loss except if it contributes to monetary growth. But it cannot continue this way, and new thinking that ties economics with the state of the planet is desperately needed.

To hear an economist say that “We are embedded in Nature” and “nature is more than a mere economic good,” as this report does, is a good start.

This extensive report (full report is 600 pages) may be viewed in a variety of formats:

Suzanne York is Director of Transition Earth.