Assessing Future Population Growth in the Anthropocene

Mar 13th, 2019 | By admin | Category: Other ResourcesBy Art Elphick, guest writer.

There is no shortage of thought on the rate of global population growth. What follows below is a brief analysis of whether United Nations projections are valid or of course, as well as questioning whether continued growth on a finite planet is truly feasible or beneficial.1) Max Roser’s Assessment (founder and editor of Our World in Data and researcher with University of Oxford)

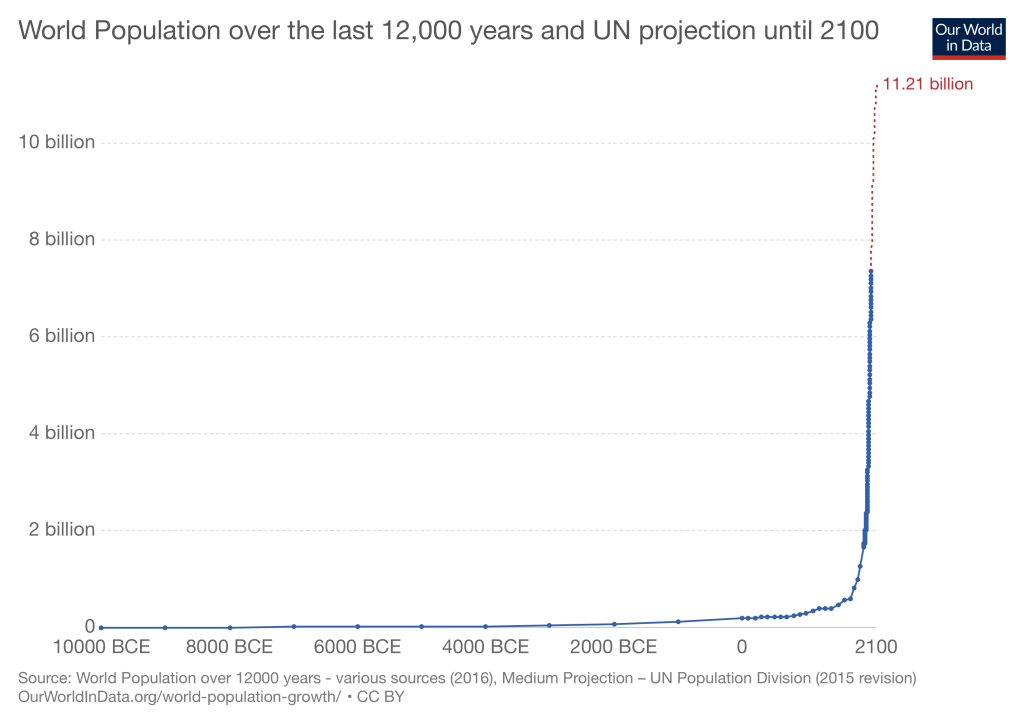

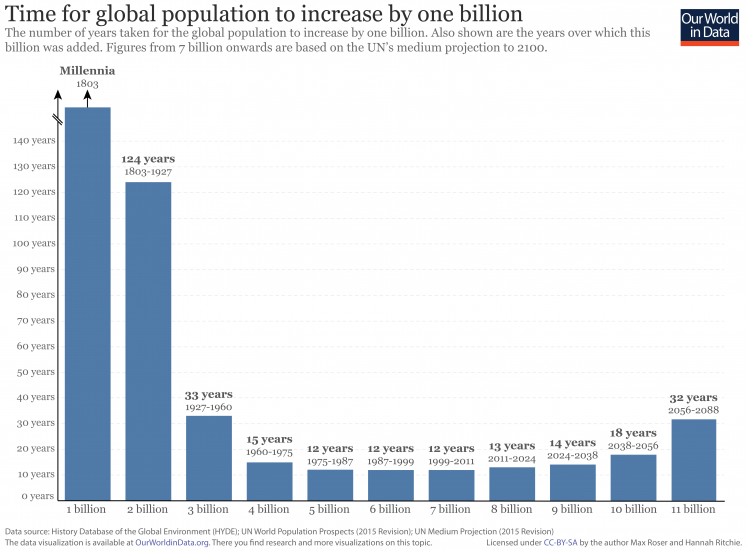

History’s fastest world population growth rate (2% per year) occurred in the late 1960s. The rate has since been falling and is now about 1%. A global birthrate of five kids per woman lasted until the end of the 1960s, but today is less than 2.5 children per woman.

The three main determinants of future global population growth are mortality, fertility, and trend momentum. While declining fertility reduces the population growth rate, increasing life expectancy around the world and falling child mortality increase the rate. Population projections can never be certain because nations may change the momentum of the current trend at any time.

Fertility corresponds to the socio-economic development and the wellbeing of women. Developed nations were first to experience falling birthrates. By 1950 their fertility rates had already declined to less than three children per woman, and Europeans and Northern Americas have since gone under the replacement rate (2.1). Fertility rates started to decline in Asia and Latin America in the 1960s with several nations now under the replacement rate. Africa, where poverty and lack of education persisted longer, was last to see lower fertility rates, though their rates too have been decreasing since the 1970s.

The rate of natural population increase is determined by births and deaths. Where fertility is high, population growth is high, but as health improves around the world, death rates fall. Since 1951, the most widely referenced population assessments are the UN’s World Population Prospects, published every two years. They are calculated mostly from each nation’s demographic data. What is considered the most likely scenario is the Medium Variant projection by nation, but the forecast also includes high and low variants that usually range about 0.5 higher or lower than the medium variant.

Nico Keilman from the University of Oslo studied two growth drivers to help explain errors in UN estimates. He says the UN under-estimated both the rapid fall of world fertility and the rise of global life expectancy which pull the net growth rate in opposite directions, thus resulting in fairly accurate global forecasts. On a regional level the study finds that “not surprisingly, problems are largest in pre-transition countries, and especially in Asia.” He said the “projection makers have been too pessimistic about future mortality” and “predicted life expectancy levels were too low on average – much too low in many cases.”

Several other institutions make their own projections, including the U.S. government, the Population Reference Bureau (PRB) and others. The International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) and the Wittgenstein Centre publish a set of highly respected and influential estimates which the author calls the WC-IIASA projections. They modify the UN data by factoring in the ideas and assessments, especially those concerning education levels by nation, of 550 demographers from around the world.

The researchers developed four basic scenarios and a larger number of combinations based on these scenarios. The middle scenario, called GET, is moderately optimistic and is considered the most likely to be right. It assumes that underdeveloped and developing nations will follow a typical path of educational expansion, as the more advanced economies did in consort with lowering birthrates. Instead of giving the current WC-IIASA forecasts, Roser refers us to the journal Nature which publishes them routinely.

2) Sanjeev Sanyal’s New York Times Assessment (2013)

Sanjeev Sanyal, the global strategist for Deutsche Bank, said the U.N.’s latest forecast is most likely too pessimistic. His forecast is that global fertility will fall to the replacement rate in less than 15 years with world population peaking about 2055, at 8.7 billion. Some demographers and many authors share his view that the UN’s growth projections are too high.

3) My Assessment

I very much hope that Sanyal is correct about the U.N.’s latest population forecast for 2050. That would be great news for our environmentally challenged planet.

Darrell Bricker’s book, Empty Planet (co-authored with John Ibbitson) laments a great population decline that he believes is spreading to nations around the world. His apprehensions seem foolish to me. 7.6 billion chimps could not overfish the oceans, destroy the reefs and estuaries, deforest the lands, kill off millions of species, turn savannas into deserts, pollute the environment with greenhouse gasses and toxic refuse, etc. These problems stem not only from population growth, but more from the phenomenal growth of human activities.

Perhaps the best measure of the growth of human activities is Gross World Product, which for the last two hundred years has been doubling on average every 20 years. Twenty years from now we will about double the number of vehicles on the planet, the number of plane and boat trips, the tons of fossil fuels we burn, the electricity we generate, etc. Bricker seems oblivious to all such environmental assaults in his calls for higher birthrates.

But Bricker reflects a growing trend. At least 56 nations now offer incentives for families to have more children, and most current books and articles that note falling birthrates seem to regard that trend more as a problem than a blessing .

What’s more, a 2017 New York Times article claimed that economic growth requires population growth. Before you accept that maxim, consider this:

Where people can migrate, they go where the jobs are. That creates demand for more infrastructure, housing and services, all of which further spur the local economy.

But does that growth enrich the region or its citizens?

Much of the growth involves catching up with the needs of expanding populations for schools, homes, roads, etc. Until the supply catches up with the growing demand, high growth areas suffer more sprawl, habitat destruction and inflation.

In places that don’t need new houses, infrastructure, and public services, people can spend the savings to improve their homes, communities, and quality of life. For example, rents and home prices in Italian towns where birthrates have long been very low range about 8 to 10 times lower than the cost of similar housing in California, my home state.

If our economic system requires endless growth in order to thrive, we must change that system rather than continue on an unsustainable path.

Art Elphick is a retired technical writer and college instructor who gives quarterly sustainability seminars at UC San Diego

![[Photo credit: James Cridland, Flickr/Creative Commons]](http://populationgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Crowds.jpg)